The human brain is a remarkable organ, capable of feats that often seem beyond explanation. One of the more fascinating phenomena reported throughout history is the rare occurrence of individuals who suddenly “know” a new language without formal learning. Could it be that the brain stores all the languages in the world and that learning merely unlocks pre-existing knowledge? In this article, we will explore real cases of spontaneous language acquisition, the scientific theories behind how language is processed and stored in the brain, and what this means for TESOL teachers.

Real Cases of Spontaneous Language Knowledge

- The Case of Ben McMahon

After surviving a coma caused by a severe car accident, Australian Ben McMahon awoke speaking fluent Mandarin Chinese, a language he had only studied briefly years earlier. Upon regaining consciousness, he reportedly spoke Mandarin as if it were his native language, despite his limited prior exposure. His English, however, seemed temporarily inaccessible. - The Phenomenon of Glossolalia

Glossolalia, or speaking in tongues, is often described as spontaneous and fluent language production, which may include speaking in languages unknown to the individual. While often associated with religious experiences, some cases report participants producing linguistic patterns that closely resemble real languages, suggesting the mind’s potential for tapping into subconscious linguistic reservoirs. - Foreign Accent Syndrome (FAS)

In some cases, people who experience brain trauma suddenly begin speaking with a foreign accent or even demonstrating fluency in a language they’ve never studied. While these occurrences are extremely rare, they challenge our understanding of how language is stored and processed in the brain.

Scientific Theories: Is All Language Stored in the Brain?

How can we explain these remarkable cases? Scientists are still trying to fully understand the mechanisms behind language storage and retrieval, but several theories may shed light on the possibility that the brain holds latent knowledge of multiple languages.

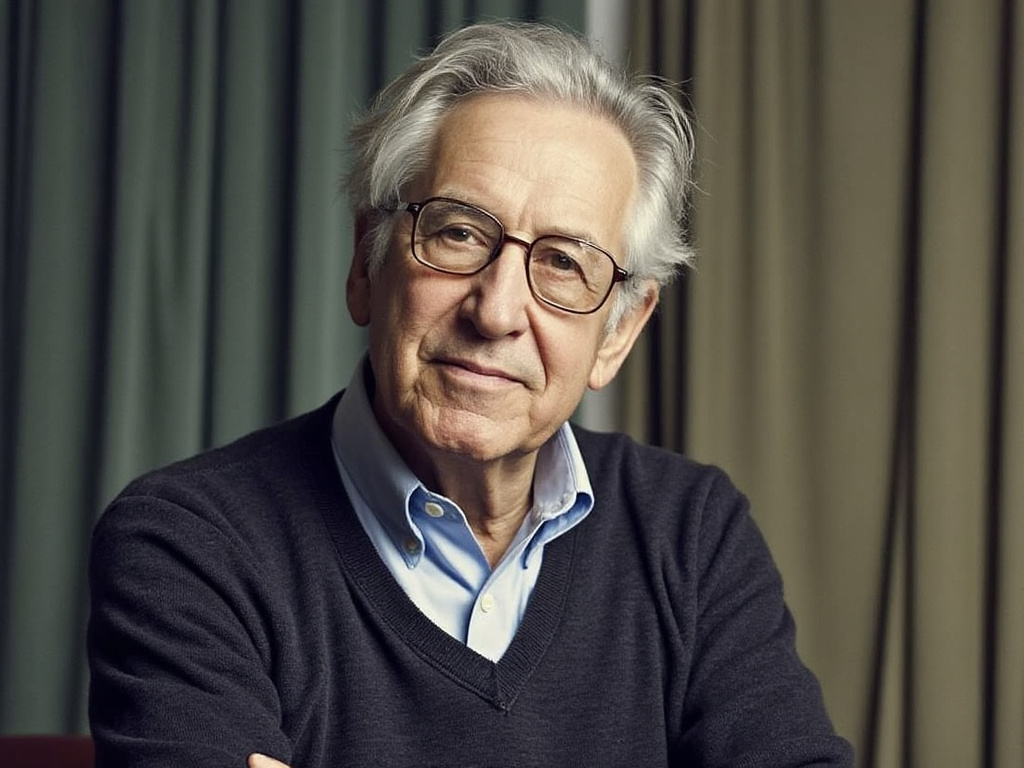

- The Universal Grammar Theory

Proposed by renowned linguist Noam Chomsky, the Universal Grammar (UG) theory posits that all humans are born with an inherent understanding of the rules and structures that govern all languages. This innate grammar enables humans to learn any language to which they are exposed during critical developmental periods. While UG focuses primarily on how children learn languages, it raises intriguing questions about whether the brain might retain the capacity to understand or even produce other languages later in life. - Neuroplasticity and Language

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections. This means that the brain can adapt and rewire itself after trauma or as a result of new experiences. It’s possible that in cases like Ben McMahon’s, brain injury triggered an unconventional reorganization of neural pathways, temporarily unlocking knowledge of Mandarin that had previously been buried in his subconscious. - Memory Reconsolidation

Memory reconsolidation theory suggests that memories, including linguistic knowledge, can be reactivated and restructured over time. The brain may store fragments of various languages, even those we’ve never actively learned, through brief exposures or passive experiences. When certain triggers, such as brain trauma, emotional states, or altered brain chemistry occur, these fragments might be brought into consciousness, creating the impression of “spontaneous” language acquisition. - Quantum Cognition and Language Storage

An emerging area of cognitive science, quantum cognition, explores how the brain might function using principles analogous to quantum mechanics. Some theorists propose that the brain can store vast amounts of information, including languages, in a state of superposition—essentially, many possibilities existing at once until a trigger collapses one possibility into reality. In this view, learning a language might not involve acquiring new information but unlocking access to information already present at a subconscious level.

Implications for TESOL: Learning as Unlocking Knowledge

What does all of this mean for language learning and teaching? If the brain does indeed hold the capacity for all language, TESOL teachers can approach language education not just as a process of acquiring new knowledge but as one of unlocking pre-existing cognitive abilities. Here are a few key takeaways:

- Language Learning as Activation

If we consider the brain as a repository of latent linguistic knowledge, then the process of language learning is more about activating and connecting neural pathways than memorizing new rules or vocabulary. By using immersive techniques, storytelling, and creative exercises, TESOL teachers can tap into students’ potential and make language feel familiar, even if it’s “new.” - The Power of Neuroplasticity in Language Acquisition

The brain’s capacity for neuroplasticity means that, at any age, students can develop new neural connections that support language learning. Techniques like repetition, pattern recognition, and engagement with meaningful content can help learners reinforce those connections, making it easier to recall and use the language fluently. - Emphasizing Multilingualism

If all languages share a common underlying structure, as suggested by Universal Grammar, learning one language can enhance the ability to learn others. TESOL teachers can encourage multilingualism by pointing out similarities between languages and helping students draw connections between their native language and English. - Using Emotional and Contextual Triggers

Since emotional and environmental factors can influence how language is stored and retrieved, TESOL teachers should incorporate engaging, context-rich activities that trigger emotional responses or simulate real-world scenarios. This could activate deeper linguistic abilities in students, making language feel more intuitive and accessible.

Scientific Backing and Future Research

Recent research into the brain’s language centers, such as the Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, supports the idea that language knowledge may be more flexible and far-reaching than previously thought. Studies using fMRI scans have shown that these areas of the brain light up not only when individuals speak their native language but also when exposed to unfamiliar languages. This suggests that the brain may possess a latent ability to process a broader range of linguistic input.

Further research into neuroplasticity and spontaneous language acquisition may one day reveal more about the brain’s capacity to store multiple languages. Until then, TESOL teachers can continue to foster creativity and exploration in the classroom, allowing students to unlock the linguistic potential already present within them.

Conclusion: The Brain as a Linguistic Vault

The human brain is a complex and mysterious organ, capable of remarkable feats, including spontaneous language knowledge in rare cases. While we may not fully understand how or why this happens, evidence suggests that the brain holds more linguistic potential than we realize. As TESOL teachers, we have the exciting opportunity to help students unlock that potential, using the brain’s natural abilities to make language learning a process of discovery rather than rote memorization.

In the future, we may learn that all the languages of the world are, indeed, stored within us—waiting to be unlocked with the right triggers, methods, and teaching approaches. Until then, we can continue to push the boundaries of language learning, fostering curiosity and creativity in the TESOL classroom.